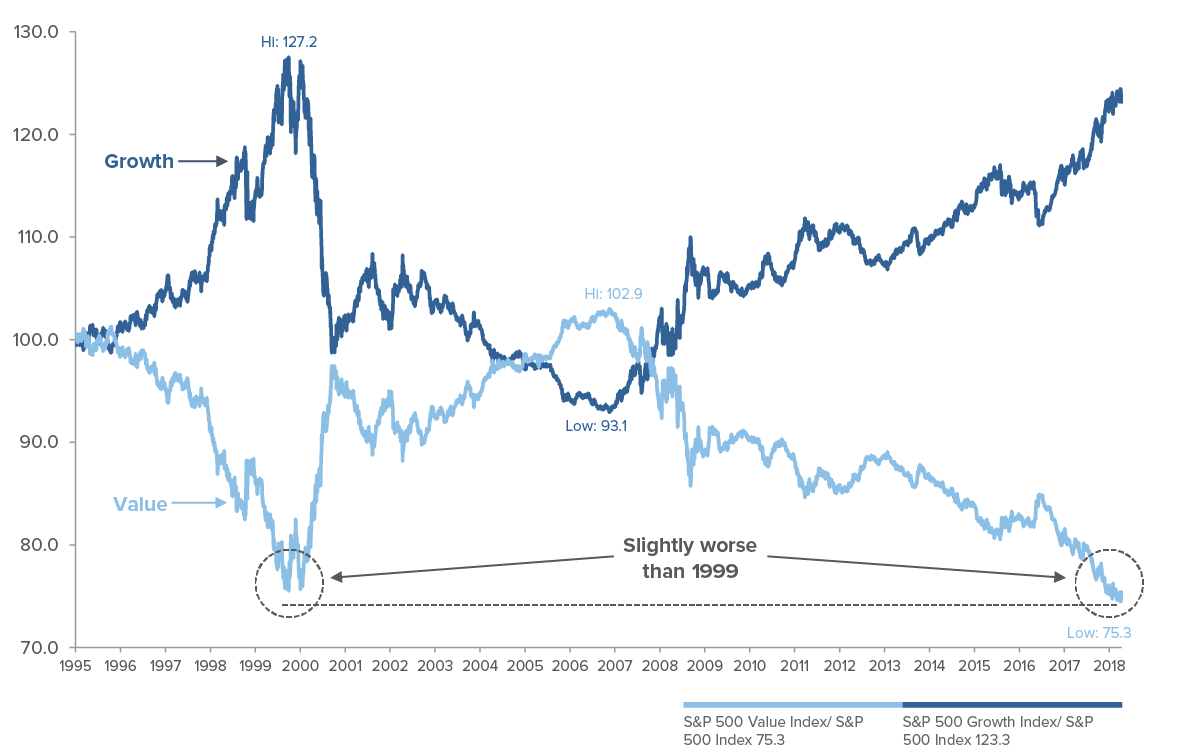

- The performance disparity between growth and value has not been this stark since 1999, at the peak of the tech stock bubble

- While growth valuations are more reasonable than tech stocks in 2000, the growth stock p/e in the market has never been higher

- Value has outperformed growth 76 percent of the time after value underperformed to a similar degree over a five-year period

Julian Robertson, a victim of the tech stock euphoria

It was an unseasonably warm 58 degrees in New York City on March 30, 2000. Winter white was just a faint memory on that Thursday, and the thoughts of bustling commuters had turned to spring. All was not balmy in the canyons of Wall Street, however, as the shock heard around the investing world had been announced that morning. Before the New York Stock Exchange opened, value investing legend Julian Robertson, age 67, announced that he was calling it quits, and would return the $13 billion that he managed to his 700 shareholders. He planned to shut down his fund and walk away.

At his fund’s peak in 1998, Robertson managed $22 billion, but he had seen withdrawals of $8 billion over the previous two years, including $1 billion in the first quarter of 2000. His fund had lost 19 percent in 1999, badly trailing the 21 percent gain in the S&P 500 index. He had lost another 14 percent in the first quarter of 2000. The New York Times summed up his predicament the day after his announcement, saying that Robertson “had essentially decided to stop driving the wrong way down the one-way technology thoroughfare that Wall Street has become.”

Robertson, a giant of the hedge fund and value investing worlds for more than 30 years, was a casualty of the technology stock euphoria that the prior five years had wrought on traditional value investors. “I’m not going to quit investing. I don’t mind people calling me an old-economy investor, but it doesn’t go over well with the clients,” Robertson noted in his farewell.

1994: The dawning of a painful new era for value investors

Main Street discovered the internet in late 1994, and the tech stock mania caught fire in mid-1995 with the initial public offering of Netscape, and the release of Microsoft Windows 95. Over the next five years, the buying and selling of stocks turned from a staid and courtly cottage industry into a full-blown national obsession. Newbie investors boasted of which tech stocks they owned, which ones they were going to buy, and how much money they were making. Tech stock investing clubs became more popular than fantasy football leagues for the average Joe, and cocktail parties became stock-tip-swapping gatherings. The new business of online trading brought stock trading to the American kitchen table. Stock valuations rose into the stratosphere. Investors felt like they were geniuses that could never lose.

As a frustrated value investor, Robertson found himself in good company that spring of 2000, as the market had seemingly lost confidence in many legendary value managers. The members of that maligned group were staunch holdouts from the high-flying tech stock investor party, and the outsized risk that they knew would cause the inevitable comeuppance. Warren Buffett’s book value, his preferred measuring stick for his own investor performance, rose a paltry 1 percent in 1999. Robert Sanborn, the once-hot Oakmark Fund value manager, resigned the week before Robertson closed his fund, after losing 11 percent in 1999.

All over Wall Street, value managers with stellar long-term records were now seen as dinosaurs in the new tech stock era. Mario Gabelli, Mike Holland, Susan Byrne, Marty Zweig and enough other famed value managers to fill a room full of Wall $treet Week couches, all faced pointed questions from wealthy investors as to why they were teetotalers at the tech-stock frat party. Some even concluded that these value managers had permanently lost their investing edge. The feeling on both Wall Street and Main Street was that a new era had passed these legends by.

Value stocks severely underperformed their Growth stock counterparts over this five-year period ended March 31, 2000. The Russell 1000 Growth index gained 298 percent over those five years, compared to the Russell 1000 Value index, which gained just 158 percent. But of course, as revenge is a dish most often served cold, the wisdom of time revealed to the investing world that a new era had not passed value managers by.

2000s: The decline of tech and Value’s comeback

Although few knew it at the time, the tech stock mania had peaked on March 9, 2000, three weeks before Robertson shut his doors. Value so badly underperformed Growth in this period that a reversion to the mean was far overdue by the spring of 2000. And revert to the mean it did. Over the next five years, Value sharply outperformed Growth, gaining 29 percent compared to a 45 percent loss for Growth.

The tech-heavy Nasdaq index declined 39 percent in 2000, 21 percent in 2001 and 31 percent in 2002. It would then take 15 years until the Nasdaq index would return to its 2000 highs again. Growth and tech stock investors, both professional and individual, lost fortunes when the tech bubble finally popped, and many disillusioned investors have not returned to equity investing since.

2018: The current Value vs. Growth story

In 2018, investors are enjoying a nine-year bull market that began in the depths of the Great Recession of 2008-09 and has been rising ever since. The market has been driven by steadily strong economic growth, low interest rates and inflation, and very low unemployment. However, a similar dichotomy has developed below the surface of the equity market between the performance of value and growth. It may ring the ear as a strong echo from the great tech bubble of a generation past.

Market excesses never repeat themselves, but they frequently rhyme. Although the public has not returned to stock trading as they did a generation ago, the rise of index funds and ETFs has been funneling large amounts of new investor capital to the largest and most popular tech household names for close to a decade.

Although the valuations of the most popular high-flying growth stocks are more reasonable these days, the performance difference between growth and value stocks is no less vast than in 1999. 2018 has been another bad year for value stocks, rising only 2 percent compared to a 15 percent gain for growth. Over the past five years, growth performance has doubled the gain of value, up 123 percent vs. 69 percent. The persistence of underperformance by value has been so stark in this market cycle that many investors are wondering, as they did a generation ago, if value investing is structurally broken.

Typically, value stocks perform well during periods of strong economic growth. The combination of rising interest rates, rising inflation and strong earnings growth are normally a boon for value stocks. Historically, value stocks have handily outperformed growth stocks, whether looking at the last 40 years or the last 80 years. But this has not been the case for the last decade.

S&P 500 Growth and Value relative price performance (vs. S&P 500) past 25 years

Price ratio: Style / S&P 500. Since 1995

The underperformance of value also has been very severe on a global basis. In the MSCI World Index, value has given up its entire 40 years of outperformance to growth. In the U.S., value has retraced the entire 19-year rally versus growth since 2000 and has returned to the price ratio versus growth seen in 1999. Growth versus value is at an extreme last seen in the exact month that value began a seven-year rally of outperformance. History may be saying to expect mean reversion soon, as value has outperformed growth 76 percent of the time after such a poor showing over a five-year period.

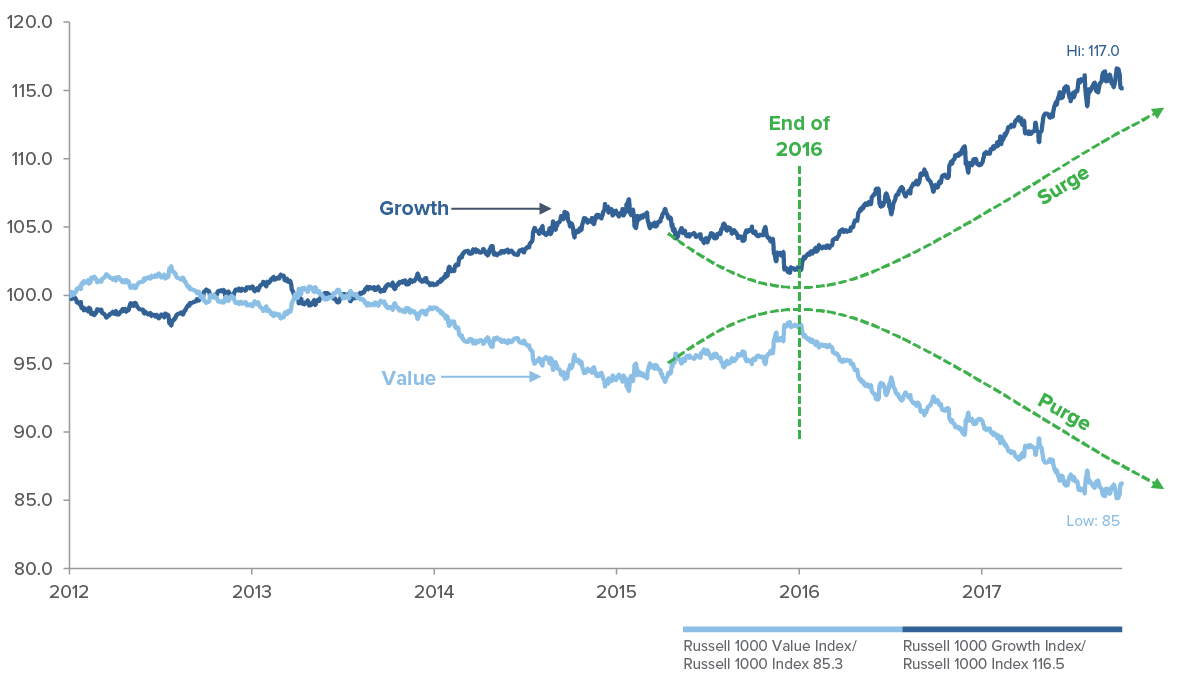

The difference in growth valuations versus value valuations is also at its highest point since 1999. Growth p/e is 7.7 multiples higher than value, which was only seen before during the 1999-00 dotcom bubble. At 25x, growth p/e has never been higher, except for 1999-00. The divergence between value and growth has been acutely sharp since December 2016, when a parabolic divergence began. The same parabolic divergence has been seen globally as well.

Russell 1000 Growth and Value relative price performance (vs. Russell 1000) past five years

Value underperformance vs. growth over the last five years is at an extreme, and has only entered this territory five times before, in 1935, 1938, 1992, 1998 and 2011. Although the 1998 occurrence was an early sign, in all five of these time periods, value strongly outperformed growth over the next five-year performance period.

What will happen in the next chapter?

In summary, while the names of the tech stock behemoths have changed since 2000, the vast outperformance of growth versus value is very similar. Looking at history, the stark divergence between growth and value in 2000 was screaming for a reversion to the mean. The market may be shouting that loudly today as well. While we are certainly not predicting a crushing correction for the market as a whole like we saw in 2000-01, we do see very good reasons for a rotation from strength in growth stocks moving to strength in value stocks.