Industrial production in the United States has been in decline for nearly two decades. But a convergence of policy choices may create the conditions for new, accelerated industrial growth. Changes to tax policy, a new position on tariffs, and an easing of fiscal conditions could set the stage for growth for decades to come.

Industrial Production Slows in 21st Century

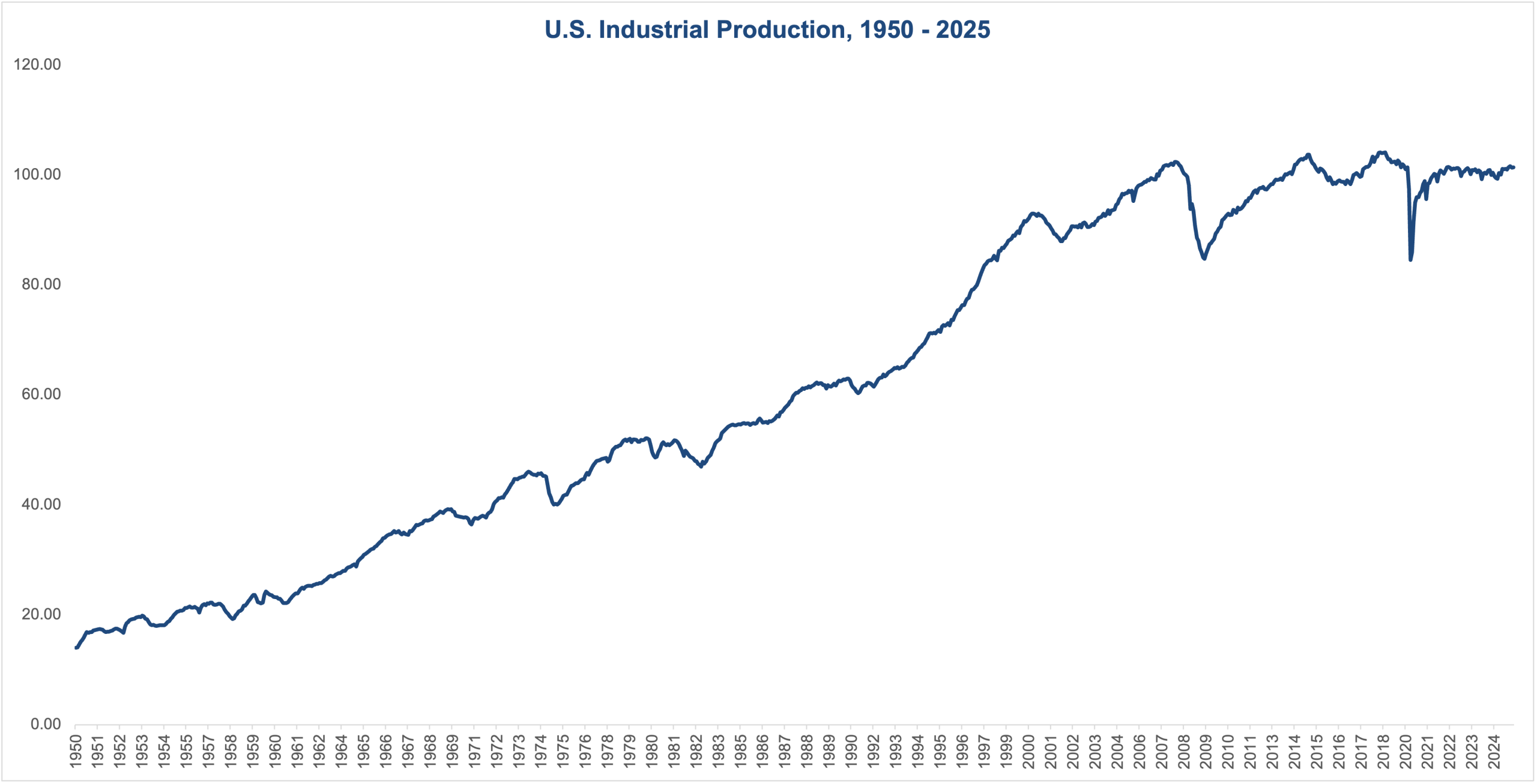

From 1950 to 2007, US industrial production rose more than seven-fold, or 3.5% a year. The post-war economic boom initially drove production higher, with pent-up demand, rising labor force participation and increased defense spending helped make the United States the global dominant industrial producer. Energy shocks and inflation in the 1970s slowed the rate of growth, but automation and technological optimization spurred industry in the 1980s and 1990s. After the dot-com bust, production continued to rise thanks to globalization and a credit boom.

But since the Great Financial Crisis, industrial production in the United States has waned. Due to the mercantilist policies of many of our largest trading partners and a commitment within the U.S. to a neoliberal economic policy, industrial production has declined by 0.1% annually since peaking in late 2007.

In exchange for cheap imports, the US has eroded its industrial base and middle class while creating significant economic and national security vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities were brought to the fore during the COVID era, during which supply chains were snarled by a reliance on imports for a number of key manufacturing inputs. Military engagements in the Middle East and Ukraine highlighted additional strains, with U.S. munitions depleted at rates that the defense industry, which relies on the broader domestic industrial base for intermediate inputs, has proven unable to replenish at a pace sufficient to maintain strategic deterrence.

While we have witnessed impressive growth recently in in non-residential fixed investment, essential to increasing U.S. industrial capacity, much of that growth has been related to the boom in artificial intelligence and data centers. Investment in industrial equipment, transportation equipment, and commercial structures has shown no growth.

To truly reinvigorate the industrial base and arrest the stagnation in industrial production, greater investment is needed in the core of the industrial economy. The stars may be aligning for an industrial boom in 2026 in part due to several key policies being implemented by the administration, as well as a more accommodative Federal Reserve.

New Incentives to Invest

First, the U.S. Budget Bill of 2025 incentivizes domestic investment by allowing for full and immediate expensing of investment in machinery, equipment, R&D and new manufacturing facilities, rather than spreading deductions out over many years. This means that when a company purchases qualifying capital assets such as production line machinery, automated manufacturing tools, or other equipment, it can deduct the full cost in the year it is placed in service instead of depreciating it over its useful life. Immediate expensing improves cash flow and lowers the after-tax cost of capital, making capital projects more financially attractive.

For example, expanded Section 179 expensing under the Act raises the deduction limit for qualifying equipment and property, increasing the amount smaller manufacturers can deduct upfront and reducing their cost of investment in machinery, software and production systems. i

Industry advocates such as the National Association of Manufacturers note that restoring and making permanent full expensing for machinery and equipment lowers the cost of capital investments across the U.S. manufacturing sector, aiding growth and job creation. ii

Published economic modeling by the Tax Foundation illustrates the broader macroeconomic rationale: full and immediate expensing reduces the tax bias against investment by accelerating the deduction of capital costs, which in standard economic models leads to a larger capital stock, higher GDP, higher wages and more employment over the long run. A Tax Foundation general equilibrium analysis, for example, estimated that a full expensing regime could increase the long-run level of GDP and private capital stock, with corresponding gains in wages and jobs compared with traditional depreciation rules. iii

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, these incentives are expected to reduce the tax burden on U.S. companies by $118 billion in 2026 and $502 billion over the next 10 years, underscoring the scale of expected relief and the intent to boost investment and productive capacity in the U.S. economy. iv

Protective Tariffs, Domestic Investments: The American System

Second, the current administration is turning away from neoliberal economic policies and towards what became known as the “American System.” Originally devised by Alexander Hamilton, it was a system of protective tariffs and government subsidies to protect nascent domestic manufacturing, accelerate industrialization and generate revenue for the fledgling nation. These ideas came to fruition with the Tariff Act of 1789 v and were fully fleshed out by Henry Clay and the Whig Party with a series of tariffs starting in 1816. vi

The administration has long stated its goals of reducing the trade deficit, increasing domestic manufacturing and reducing our reliance on imports. Protective tariffs are one of the tools the administration is using to increase domestic manufacturing. Import tariffs incentivize the reshoring of production by subsidizing domestic manufacturing while taxing the domestic consumption of imports. Whether the tariffs as structured will increase industrial production without negatively impacting economic growth remains to be seen.

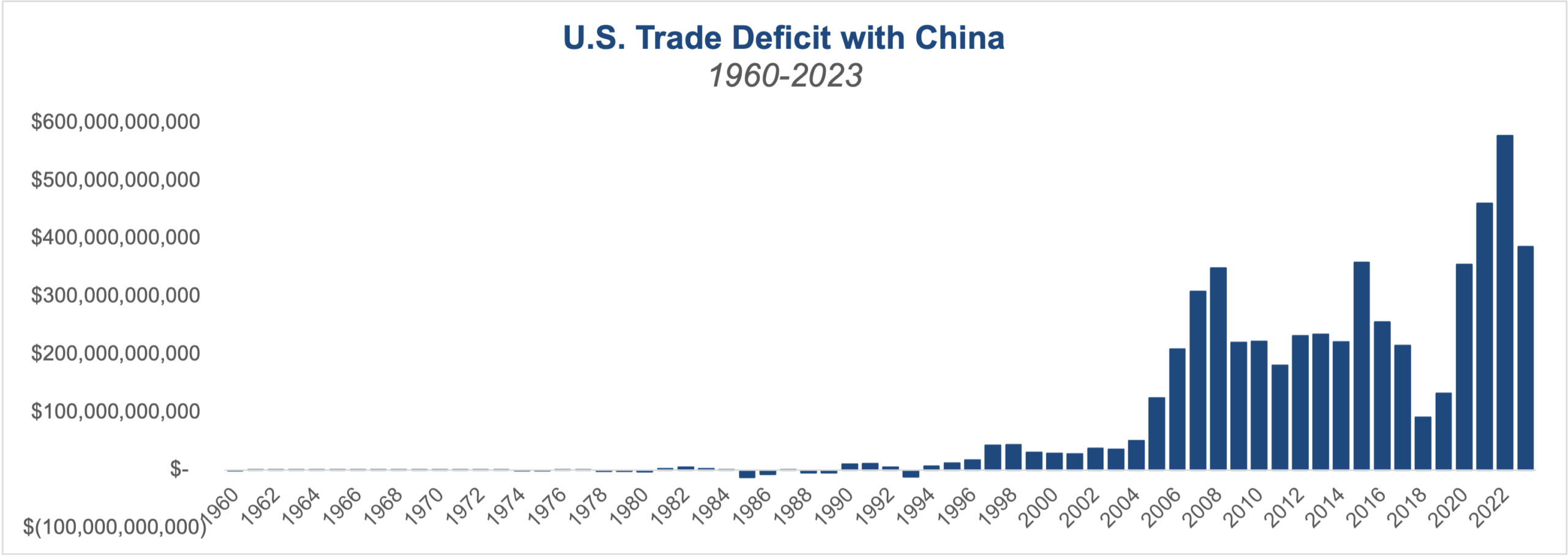

Tariffs are also key to reducing the trade deficit. Trade imbalances are a function of domestic saving and investment: When saving exceeds investment, a trade surplus is the result. A country that runs a trade surplus forces its trade partners to run trade deficits (surpluses and deficits must balance globally). Perhaps the most prominent example is China, a communist dictatorship, which tightly controls its domestic economy, subsidizing its manufacturing sector at the expense of domestic workers and consumers. This results in a large and persistent trade surplus in tradable goods, which diminishes the rest of the world’s manufacturing sector as a share of global production. vii

Beyond tariffs, we have seen the administration make investments in companies in strategic industries like semiconductor manufacturing and rare earth processing. viii At the same time, the administration has implemented price floors and purchase agreements to incentivize domestic production, insulating these industries from the monopolistic pricing practices employed by the Chinese.

Recognizing that free trade is not free when the world’s largest industrial economy behaves in a mercantilist manner, the administration is implementing policies not seen in a century in an attempt to reorient excess U.S. consumption away from imports and toward domestically produced goods, boosting domestic industrial production, as well as employment and GDP.

Falling Interest Rates Support Growth

Finally, the material reduction in interest rates over the last two years may provide a significant boost to the industrial economy. The industrial economy is highly sensitive to credit conditions, with the vast majority of capital goods, consumer goods, and working capital financed by producers up and down the supply chain as well as final purchasers.

Declining long-term yields directly reduce the cost of capital for manufacturers, which can improve the economics of large, long-lived investments such as machinery, automation, and plant expansion. Capital-intensive industries like industrials, materials, and transportation tend to see a disproportionate response as hurdle rates fall and previously marginal projects clear internal return thresholds, accelerating order activity for equipment and intermediate goods.

Second, easier financial conditions improve balance-sheet flexibility and liquidity across the supply chain. Lower borrowing costs ease pressure on inventories, receivables, and trade finance, allowing suppliers and distributors to carry higher production levels with less balance-sheet strain. This effect is particularly important in manufacturing, where production cycles are long and working-capital intensity is high, amplifying the transmission of lower rates into higher throughput and utilization.

Third, falling yields typically generate higher demand for interest rate-sensitive goods, including autos, housing-related products and durable consumer goods, which are among the most important drivers of factory orders. ix As financing costs decline for households and businesses, demand visibility improves, encouraging manufacturers to rebuild order books and expand capacity rather than operate defensively.

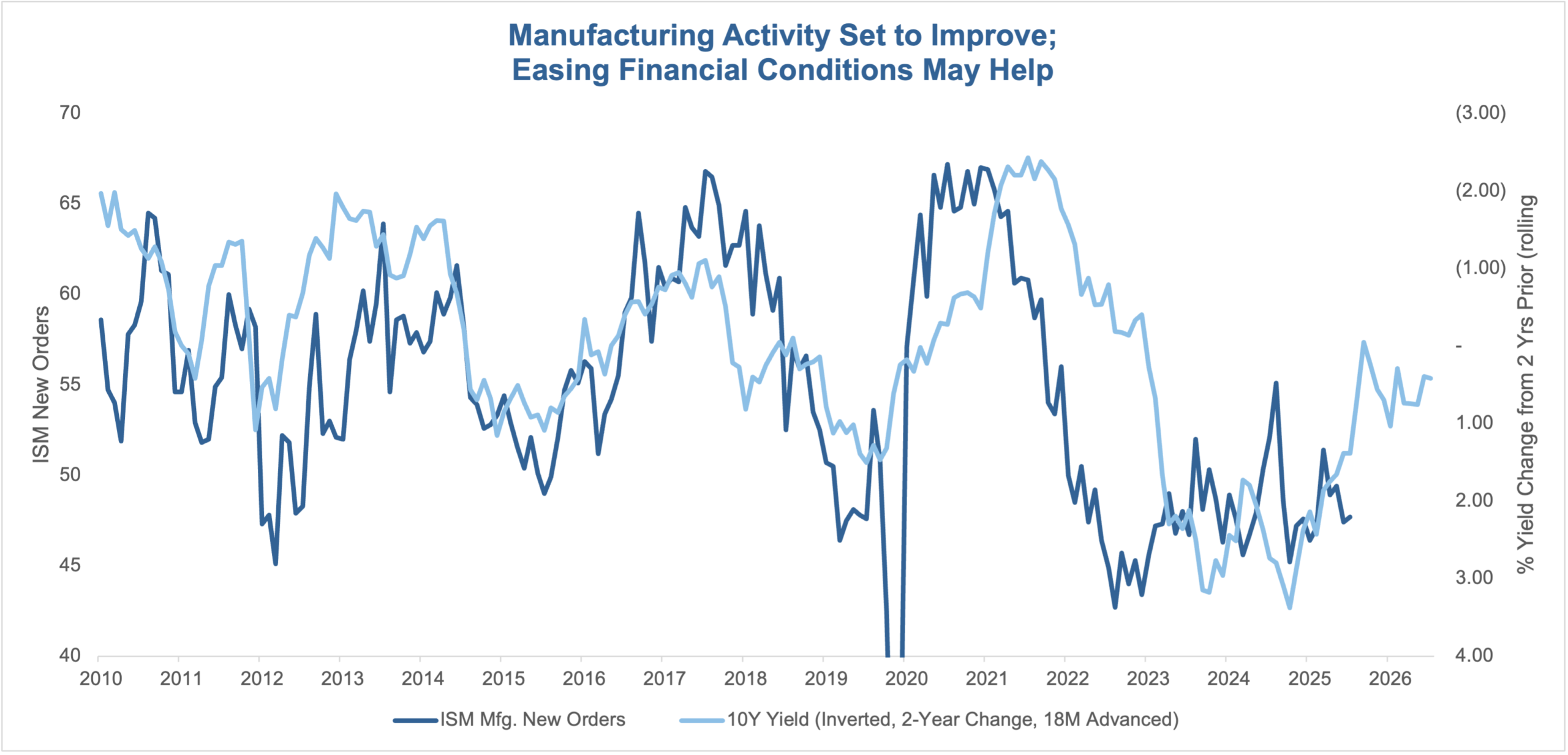

Historically, changes in 10-year yields are highly correlated with the ISM Manufacturing New Orders index, a leading indicator of domestic manufacturing activity. If history is a guide, lower rates may be stimulative to the industrial economy by themselves.

Conclusion: Reigniting an Industrial Powerhouse

Truth be told, the policy changes implemented by the Trump administration have had a rocky start, as inflation remains stubbornly high, employment and job creation have lagged, and official GDP growth figures have been inconclusive. But these policies are being implemented for the next ten years, not the next ten minutes – and there are already green shoots among manufacturers. After eighteen years of stagnation, there is hope that these policies may return the industrial sector to growth.

Kyle Martin, CFA®

Kyle Martin, CFA®