In response to a pandemic-induced sell-off in March 2020, the Federal Reserve announced that it would purchase corporate bonds, including riskier junk bonds, as part of its effort to stabilize the financial markets. Fed bond buying, along with a pledge to keep interest rates near zero for as long as needed, helped to calm the nerves of investors and to keep money flowing into corporate debt. In fact, U.S. corporations issued more than $2.2 trillion in new debt in 2020, up from $1.4 trillion in 2019.1

Corporations sell bonds to finance operating cash flow and capital investment. Corporate bonds usually offer higher interest rates — and are subject to more risk — than U.S. Treasury securities with comparable maturities. U.S. Treasury securities are guaranteed by the federal government as to the timely payment of principal and interest, but distressed corporations occasionally default on payments. Investors who rely on corporate bonds for retirement income, or to help temper the effects of stock market volatility, should consider the degree of risk they are willing to accept in their bond portfolios.

Credit Risk and Ratings

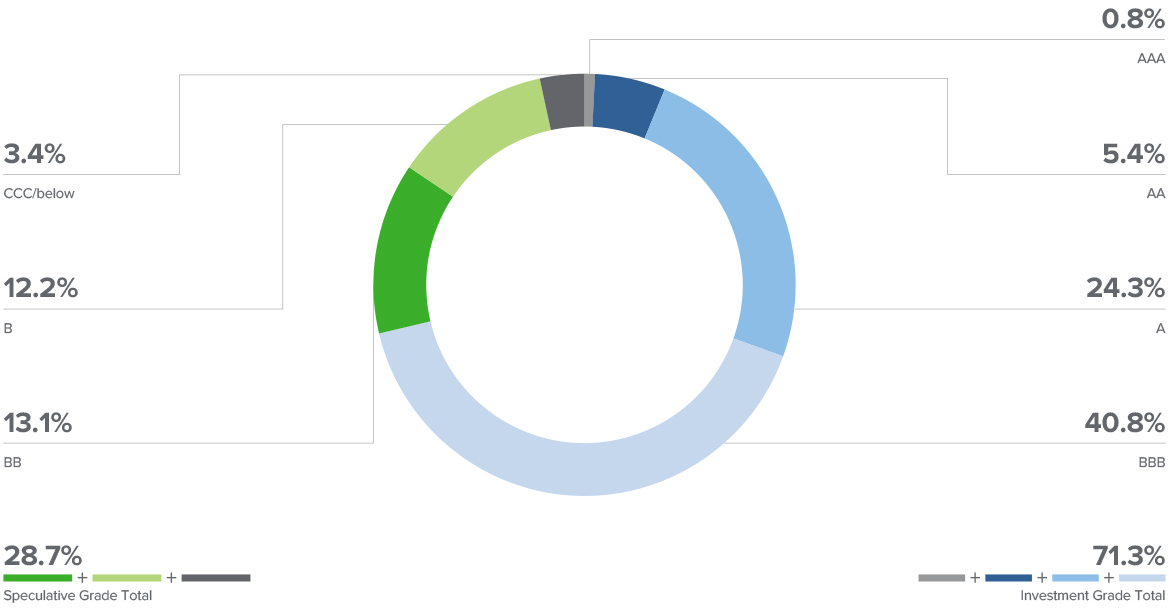

Most corporate bonds are evaluated for credit quality by one or more ratings agencies, each of which assigns a rating based on its assessment of the issuer’s ability to pay the interest and principal as scheduled. Bonds rated BBB or higher by Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings, and Baa or higher by Moody’s Investors Service, are considered investment grade. Lower-rated corporate bonds (called high-yield or “junk” bonds) are considered non-investment grade or speculative, because they are issued by companies considered to pose a greater risk of default. Bond investors generally receive higher yields as compensation for bearing higher risk.

U.S. corporate debt, by rating category (share of total)

Many factors can alter a company’s perceived credit risk, including shifts in economic or market conditions, adjustments to taxes or regulations, and changes in management or projected earnings. When a ratings agency upgrades or downgrades a company’s credit rating, or even adjusts the outlook, it often causes the prices of outstanding bonds to fluctuate.

An Uneven Outlook

Thanks to the Fed, many companies have been able to borrow at very low rates and with favorable terms, putting them in better shape to ride out the pandemic and repay their debt over time.

On the other hand, some companies in sectors that were harshly impacted by social distancing measures and lockdowns — or that were in a weak financial position before the health crisis began — are more vulnerable to credit pressures.

According to a forecast by S&P Global Fixed Income Research, the trailing 12-month default rate for U.S. speculative-grade corporate debt will rise to 9% by September 2021, up from 6.3% in September 2020. However, the risk of default is greater in hard-hit corporate sectors such as retail, restaurants, travel-related sectors, and oil and gas.2

Downgraded bonds that lose their investment-grade ratings are known as fallen angels. There was a spike in fallen angel debt in 2020, and the number of potential fallen angels (rated BBB- with a negative outlook) is projected to decline in 2021 but remain elevated.3

Thirsting for Yield

After accounting for inflation, the real yields on many U.S. Treasuries have dropped below zero, while the real yields for many investment-grade corporates are barely positive. As a result, some fixed-income investors may be motivated to invest in riskier high-yield corporate bonds.4

Investors who stretch for yield should have the discipline to tolerate the price swings typically associated with lower-quality bonds. And considering the potential for lingering economic uncertainty, investors might want to take a selective approach when evaluating corporate bond investments.